In his latest article, Peter Moore looks back on the racing and the riders at the Ulster Grand Prix in the 1930’s.

The early 1930’s continued in the same vein as the late 1920’s, with Stanley Woods still the man to beat in the senior cc classes. He won the 500cc class in 1930 aboard a Norton, with Leo Davenport winning the 350cc class.

It was only in 1934 that Woods’ and Norton’s strangle hold on the 500cc class was broken by W. F. Rusk on his Velocette.

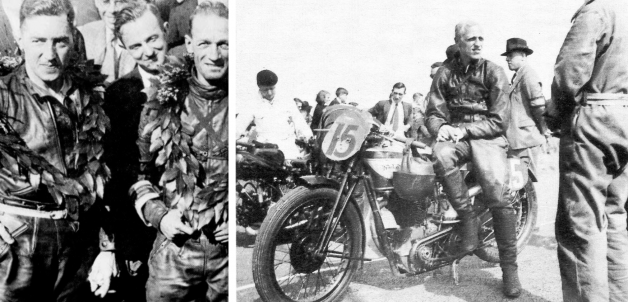

In the picture from the1930 Ulster Grand Prix, Woods remains ever-smiling, as if he has just arrived for a day out and a picnic, rather than competing in the world’s fastest road race. Davenport, the younger man, is somewhat more dashing, even if to my eyes he bears a passing resemblance to David Bowie!

1931 was the first time the ‘Governor’s Trophy’ was awarded, by all accounts the prize was a; “…trophy of truly wonderful proportions, and inscribed with a nice choice of previous names.” (Dixon, 1940).

However, the event would not be immune from the worldwide economic recession during the 1930’s, and presumably this was a factor in 1932, which was the last year Rudge Works entered the event.

From what pictures are available, though, the Grand Prix seems to have continued and even gained popularity, with crowds lining the circuit within touching distance of the bikes on Clady’s ‘Seven Mile Straight’, (today’s organisers would weep at such a sight!).

But whether events such as these represented a way to eschew ever harder economic times we can only guess.

As the Romans demonstrated, when times are hard, entertain the people – perhaps it was an opportunity for many to escape, even temporarily, to a world they gazed at with awe, at machines with fascination and at men they wished they were, but could never be. It was certainly a 20th Century version of a gladiatorial contest!

In 1935, for the first time, the Grand Prix was awarded the title of ‘Grand Prix d’Europe’ by the FIM (Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme), supposedly awarded to what the FIM regarded as the most important race of the year.

The senior class won by Jimmy Guthrie, who was sadly killed at the German GP two years later.

Following the death of Guthrie in 1937, the Norton works team withdrew from the ‘Ulster’ for that year as a mark of respect.

But Norton’s withdrawal was an opportunity for BMW, the first time the marque made an impact, with Jock West winning the 500cc class, an achievement he would repeat the following year

The number of entrants, in general, steadily declined towards the outbreak of World War II, many racers enlisted in the Forces, and many did not make it back.

It is, from a modern point of view, intriguing to know if these gentlemen racers knew or had a sense of what was to befall Europe at the end of the decade.

It seems to be a metaphor somehow for the end of an era, the finale of the plucky amateur – even though the riders and teams were anything but, and today many of the modern riders are not full-time professional motorcycle racers.

Perhaps this perception is because, in my psyche at least, the post-war period in some way marks the beginning of true modernity, or maybe it’s because it is within living memory. The exploits from the Ulster Grand Prix during the 1920’s and 1930’s seem, to me, remote and distant.

The Grand Prix was run in 1939, but the decision to proceed was uncertain, as cancellation of the event would have essentially bankrupted it.

The fraught organisation committee was split, resulting in resignations and, given the timing, it is not surprising that the number of entries across all the classes was low totalling sixty riders.

The Grand Prix did not take place during the war, and although a form of race was run in 1946, it wasn’t an international race or Grand Prix, but more a test event.

At the start, a flag draped bike was wheeled out onto the grid as a tribute to those riders who had died during the war. The 1946 event was a test for the new circuit; Clady (Mark Two).

Image: Derek Beattie (2013)

Right: Walter Rusk awais the start of the 1935 Ulster Grand Prix/ Images: Derek Beattie (2013)